20 Jun 1996 - Mayotte, Comoros Islands, Indian Ocean

I am in a different place

now. This island is a volcano. I am in the tiny village of Tsingoni, and Ali

Minihaji welcomes me into one of the oldest mosques on the island. On his

forehead is a dark round callous. He is proud of this mark. It has been formed

from years of worship. Five times a day he prays, and many times during his

prayers will he press his head to the floor before God. I am invited to touch

this spot with my finger; it is hard like the palm of my hand. I smile at this

very righteous man, and we talk about his island.

I am in a different place

now. This island is a volcano. I am in the tiny village of Tsingoni, and Ali

Minihaji welcomes me into one of the oldest mosques on the island. On his

forehead is a dark round callous. He is proud of this mark. It has been formed

from years of worship. Five times a day he prays, and many times during his

prayers will he press his head to the floor before God. I am invited to touch

this spot with my finger; it is hard like the palm of my hand. I smile at this

very righteous man, and we talk about his island.

'Al Camar' is the Arabic

word for moon, and these are the 'Djzair' L Camar' - the 'Islands of the Moon'.

What a beautiful name for a book, I imagine. There are four islands here, and I

am on the one owned by France. As I come in to land, I fly over a small round

volcanic crater. It is called 'Dziani Dzaha', and this is a place where I must

not swim. I am curious if this is more black magic, but it is not. There were

three French military divers who went in there some years ago, and they never

were seen again. It may have been due to poisonous gasses, but it was probably

because of a hole beneath the water's surface that goes through to the ocean.

The level of the water in the small volcanic crater rises and falls with the

tides of the ocean, so the water must be coming in somehow. It is strange,

however, that all three divers were lost, and that none of their bodies ever

washed up on a beach. The ocean here is deep though, I am told, and this is the

home of the coelacanth. This prehistoric fish was thought to have been extinct

for millions of years until one day a fisherman found one in his net. Several

have now been seen alive along the steep underwater slopes of the islands.

'Al Camar' is the Arabic

word for moon, and these are the 'Djzair' L Camar' - the 'Islands of the Moon'.

What a beautiful name for a book, I imagine. There are four islands here, and I

am on the one owned by France. As I come in to land, I fly over a small round

volcanic crater. It is called 'Dziani Dzaha', and this is a place where I must

not swim. I am curious if this is more black magic, but it is not. There were

three French military divers who went in there some years ago, and they never

were seen again. It may have been due to poisonous gasses, but it was probably

because of a hole beneath the water's surface that goes through to the ocean.

The level of the water in the small volcanic crater rises and falls with the

tides of the ocean, so the water must be coming in somehow. It is strange,

however, that all three divers were lost, and that none of their bodies ever

washed up on a beach. The ocean here is deep though, I am told, and this is the

home of the coelacanth. This prehistoric fish was thought to have been extinct

for millions of years until one day a fisherman found one in his net. Several

have now been seen alive along the steep underwater slopes of the islands.

Ali speaks proudly of another mosque on the island of Grand Comore. When the

volcano erupted there a few years ago, the lava flowed down the slope and into a

village. It parted before the small mosque and went around it on both sides,

before joining again on the other side. Ali smiles as he describes this event to

me; it is obvious to him that it was the will of God that this mosque had not

been destroyed.

Johan Nel drives me across

the island along winding roads and steep slopes. We go from forests of coconut

palms that shade us like a gigantic umbrella to a bizarre jungle of gnarled

trees. "These are the Ylang Ylang," Johan tells me. All around us are contorted

and knotted forms of woody vegetation with green leaves and droopy yellow

flowers. I become immediately aware of a strong and sweet odor in the air.

'Ylang Ylang' means 'flower of flowers', and the essential oils distilled from

the flowers of these trees were at one time the basis for most of the perfumes

in the world. Today, they have been replaced by synthetic substitutes, and the

demand has dropped off to almost nothing.

Johan Nel drives me across

the island along winding roads and steep slopes. We go from forests of coconut

palms that shade us like a gigantic umbrella to a bizarre jungle of gnarled

trees. "These are the Ylang Ylang," Johan tells me. All around us are contorted

and knotted forms of woody vegetation with green leaves and droopy yellow

flowers. I become immediately aware of a strong and sweet odor in the air.

'Ylang Ylang' means 'flower of flowers', and the essential oils distilled from

the flowers of these trees were at one time the basis for most of the perfumes

in the world. Today, they have been replaced by synthetic substitutes, and the

demand has dropped off to almost nothing.

Ismaiel Said Combo tells me that independence is a pretty word, but it also

has brought many problems. I don't think any country has had more coup d'etat

attempts than the Comoros. In May 1987, the leader Ali Soilihi was killed during

the coup led by Bob Denard. Denard is a very famous mercenary here, but he is

old now, or so we thought. Nine months ago, he came back again and tried another

coup. In our Comorian language, we say, "ufa djamaa harusi." In French, it

means, "la mort collective, c'est le mariage?" (the collective death, it is the

marriage). It is an easy-going approach to life; "if I am not alone, I have

comfort." It is not so bad to lose one toe, if everyone is losing one toe.

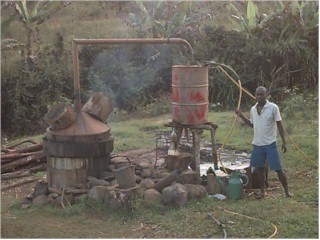

On one of the bends of the

curvy road, Johan points out a large steaming copper vat. It is being fed by

various bamboo aqueducts and rusty pipes with a wood fire at its base. The vat

is filled with 200 pounds of Ylang Ylang flower petals and some water. They are

distilled, and the steam is condensed in a water-cooled pipe that leads down

into a peculiar shaped container with different tubes and windows on it. Being a

physicist, I am extremely curious how this contraption works. One of the men is

quite keen to show me. He places his finger over one of the holes. Instantly,

the level of the oil and water in the container begins to rise, and the oil

begins to decant off the top into a small jar. He then removes his finger with a

grin, and the water which had accompanied the essential oil out of the large vat

trickles away down another bamboo aqueduct and back into the large vat to be

recycled.

On one of the bends of the

curvy road, Johan points out a large steaming copper vat. It is being fed by

various bamboo aqueducts and rusty pipes with a wood fire at its base. The vat

is filled with 200 pounds of Ylang Ylang flower petals and some water. They are

distilled, and the steam is condensed in a water-cooled pipe that leads down

into a peculiar shaped container with different tubes and windows on it. Being a

physicist, I am extremely curious how this contraption works. One of the men is

quite keen to show me. He places his finger over one of the holes. Instantly,

the level of the oil and water in the container begins to rise, and the oil

begins to decant off the top into a small jar. He then removes his finger with a

grin, and the water which had accompanied the essential oil out of the large vat

trickles away down another bamboo aqueduct and back into the large vat to be

recycled.

Johan explains to me that these small distilling operations are probably run

by entrepreneurs who have found some markets for the essential oils. Today, it

is mostly to tourists, but these oils are also still used to anoint the bride

for 'le grand mariage'. This lavish 3 day marriage ceremony is very important to

Comorians. The women in Comoros are the ones who will inherit a family's wealth.

Their father begins building a girl's marriage house when she is born. Sometimes

the marriage ceremony can bankrupt a family, but it is also a good way of

distributing wealth throughout a community. Today, many marriages in Comoros end

in divorce. A Muslim man can divorce his wife simply by saying, "I divorce you."

However, the divorced wife keeps her house and car and any other valuable

possessions, so this can become a costly initiative for a man who has 4 wives.

As I walk through the little streets of Pamanzi, I notice the faces of many

women covered with light-colored beauty masks of powdered sandalwood. It is

almost as if they feel more comfortable with the masks than without them,

especially the young girls. Many colors and traditions here have there origins

in Arabia, Persia or East Africa, but I notice the women have a gentle power and

confidence about them. Perhaps this confidence comes from their traditional role

of controlling the family's purse strings, but today that may also be changing,

as banks prefer to make loans to men.

The airport in Mayotte must be one of the friendliest I have visited. The

very polite French Gendarme greets me upon arrival and asks to see my pilot's

license. I tell him that I am not exactly sure where it is, because no one has

ever asked to see this before. I eventually locate it and present it to the

officer. He thanks me most politely and asks if I would like my passport stamped

as a souvenir. I normally could care less about this, but I am so enchanted by

this polite man, that I say, "Yes". One of the great secrets on this trip has

been the fact that pilots don't need Visas when they visit different countries.

One must have a flight clearance or a flight plan, but then on the ground, you

are admitted as a part of the plane - its crew. In Africa, however, it is not

always easy to get a flight clearance, so too often, I have arrived with neither

a flight clearance nor a Visa. I had neither upon arrival in Comoros, but it

doesn't seem to matter in the slightest. The rules keep changing all the time

from place to place, and it seems to be much easier to not know what they are.

There is a freshly cut section of grass on the corner of the airport near one

of the volcanic craters that I flew over. At the base of the lava hill, there is

a little flying club ensconced in large willowing trees. I taxi the plane across

the grass to in front the club. There are no other planes around, but I am

greeted and given the key to the club in case I need anything. Sometimes, when

you come from a place where you are always a little bit scared, to a place where

everything is safe and relaxed, you can't quite believe it is true. I start to

giggle to myself that this must all be a dream and that this can't be as easy as

it is. I set up my tent on the lush grass and spread my rain canopies across the

wing. I also have 5 little folding chairs that I carry in the back of the plane.

They are for entertaining guests, and they are positioned out in a semi-circle

beneath the canopy. Some young Comorian boys bring beef brochettes from a nearby

restaurant. They are all aspiring pilots, and we sit beneath the wing talking

about life in the Comoros.

As the sun rises the following morning, the thundering roar of tremendous

piston engines shakes the ground and passes swiftly overhead. The sound is too

exciting and too foreign. It is a sound I have not heard for a long time. I

watch the four-engine DC-4 pass in the warm early morning light behind the

volcano, then swoop in low across the water to land. The craft pulls up heavily

next to me on the grass. She is like a gentle old lady. The engines tick and the

propellers swirl like gigantic fans as they come to rest. This is a relic from

the past, and I cannot imagine what it is doing here. A sturdy looking man with

a red bandanna around his neck and short cropped hair appears at the cargo door

and stares out at this new place. I know the look. It is that look of a

successful warrior who has accomplished his mission. I can tell this man is

different. I walk up and introduce myself. He pauses, then smiles at me and

says, "I know you. You have spoken to me, but I have never spoken to you." I am

startled. The rest of the crew appears. They have been flying all night from

South Africa, then from Zimbabwe, and they are exhausted. They supervise the

unloading of all the fresh food from France. This man's name is Mike Snow. I do

know the name. This is the man who flies in one of the bad places - Zaire. I had

left a message on his answering machine a few years ago before I went there; I

wanted some advice.

Mike tells me that when he was flying cigarettes in Zaire, it was very

important not to have all your papers in order. "That is a lawless land," he

says. "If you have all of your papers in order, they don't know what to do, and

they can become confused and angry." You must always leave one small thing out

of order, so that they can find this and make you pay something. Mike is one of

these guys who could never live in Europe. He hates signs telling him what to do

and where to go. "They control your thinking," he says. "In Europe, if it's not

compulsory, it's forbidden. This is why I like Zaire. You are your own law, and

you make up your own rules." Mike confesses that this is a bit of an acquired

skill - sort of like an acquired taste for certain wines or strong cheese.

"You've got to be a character to be there - your own person - and people like

that don't like other people like that," he says. "Zaire brings out the best in

people, but sometimes the best is the worst. Or it brings out the worst, but

that worst is the best. It is a bit like that Zen thing - when things are,

they're not, and when they're not, they are. There is something about that place

- 'tres terrible' as it is - that makes me still desire it. It is like a bad

woman that attracts you. You know you shouldn't go there, but you do." Mike is

49 years old. He spent 8 years in the SAS in Europe and Borneo jumping out of

airplanes. With his British Midlands and South African accent, he tells me,

"Maybe I am living out a fantasy, but thundering across Africa in the middle of

the night in a 51 year old aircraft just does something to me."

The early Arab traders must have carried many myths and legends about these

beautiful and exotic islands with them on their journeys between Africa and

Arabia. In one of them, King Solomon had given a ring to a 'jinn' (or spirit) to

carry to his beloved Queen of Sheba. The jinn dropped this ring on his way, and

it gave rise to the mighty Comorian inferno 'Kartala' - one of the largest

active volcanic craters in the world.

Ishmaiel shares with me another Comorian saying - 'kali-kali kalihomo htswa.'

In French, one would say, "le soleil qui brille avec ardeur, a vite fait de se

couche." (The sun which burns brilliantly, sets quickly). He tells me that the

sun sets very quickly near the equator, and if you search the extreme, this is

as true for the life as it is for the sun. "Look at JFK, or anyone who is

intelligent or mean or beautiful or lucky. They do not stay long; they die. It

is necessary to be in the middle," he says. I sense that Ishmaiel's proverb

understands that in our minds, the brightest flames will burn the shortest; if

it is beautiful and interesting, then it has to go down. I am not sure that I

understand this, but it seems to be true.

Mike Snow climbs back up into his DC-4. He smiles down at me and yells me one

last thought. "Tell me, if you work on your mind with your mind, how can you

avoid the immense confusion?" I stand back and listen to the staccato commands

exchanged between the members of the crew. Then the first of the four giant

radial engines begins turning slowly until it catches and explodes into a full

rich roar of smoke and sound. The words 'thundering across Africa' come to mind.

I don't know where Mike is now, but I would not be surprised if he were back in

Zaire.

Tom Claytor