28 Jun 1996 - Zanzibar

I keep reminding myself

never to have an expectation of a person nor a place. As I take off from the

Comoros, a voice calls me on the radio, "Au revoir," he says. It is not the

traffic controller, but someone else. I reply, and he comes back again, "C'est

joli, Mayotte" (it is pretty, Mayotte). "Yes," I reply. The tiny islands

disappear and an ocean surrounds me again. I sometimes chuckle to myself over

the ocean, because I know how futile it would be to expect anyone to come and

look for me if my engine decided to stop. It also occurs to me that I am always

saying good-bye to people. I don't like good-byes; I prefer "Au revoir," but

where I am going now, no one will understand that. I look forward along the

horizon and wait for the coast of Tanzania to appear.

I keep reminding myself

never to have an expectation of a person nor a place. As I take off from the

Comoros, a voice calls me on the radio, "Au revoir," he says. It is not the

traffic controller, but someone else. I reply, and he comes back again, "C'est

joli, Mayotte" (it is pretty, Mayotte). "Yes," I reply. The tiny islands

disappear and an ocean surrounds me again. I sometimes chuckle to myself over

the ocean, because I know how futile it would be to expect anyone to come and

look for me if my engine decided to stop. It also occurs to me that I am always

saying good-bye to people. I don't like good-byes; I prefer "Au revoir," but

where I am going now, no one will understand that. I look forward along the

horizon and wait for the coast of Tanzania to appear.

Tanzania is like an old friend for me. I remember many years ago when I was

in Dodoma with my piki-piki. They speak Swahili there, and this is such a

beautiful language; you almost sing it rather than speak it, and it is

wonderfully pragmatic in its creations. A tractor is a tinga-tinga,

because that is the sound that it makes, and a motorcycle is a piki-piki,

because that is the sound that it makes. The police officer stopped me as I was

on my way through town to the airport. He did not smile, and he walked around my

piki-piki and me, inspecting us slowly. I could tell there was hope in his eyes

as he announced that the tail light on my piki-piki was not working. Soliciting

bribes is often the best way to supplement one's salary in Tanzania, and the

police are very good at it. Unfortunately for this policeman, I was having a

good morning. I explained to him that all the street lights in the town were

off, since it was daytime, so how could the tail light on my piki-piki possibly

work if there was no electricity. He looked back at me with lifted eyes. This is

very much a game of the eyes. Mine were open and naive. Then he said to me,

"Go," and pointed with his lips in the direction I was to proceed.

In the afternoon, he was there again, by the side of the dusty road. I was

not surprised that he stopped me. I was fresh meat in town, and why shouldn't I

be tested? He wanted to inspect the documents for my piki-piki. He looked

closely at my insurance, registration, carnet de passage, and license. All of

these, I had typed up myself in Kenya, but I have a rubber stamp which says

APPROVED and all of these documents had been APPROVED. He was satisfied.

He then examined my passport. One of the most important documents to carry in

Africa is the Yellow Vaccination Certificate (to verify which diseases you have

been vaccinated for), and I have two of them in case I lose one. Every six

months, one has to renew the Cholera vaccination. I do not wish to risk the

exposure to AIDS nor Hepatitis from bad needles, so I have another stamp which

says MEDICAL and approves both of my vaccination certificates for renewed

Cholera vaccinations every six months. Both of my Yellow Vaccination

Certificates fell out of the back of my passport; I had forgotten to put them in

different places after renewing them. I could see his eyes focus on these as he

collected them from the ground. "Why do you have two of these?" he asked me. I

was having another good morning, so I explained to him that one was for me, but

the other one, of course, was for my piki-piki, so that it didn't carry diseases

from place to place. I could see the wheels turning inside of his head, and

again my eyes were gentle and innocent. He returned my documents, pointed his

lips, and said, "Go."

The following evening, I passed the same way, but the policeman was not

there. I did notice about 3 or 4 vehicles stopped on the side of the road, and I

carried on. I was in the kitchen of a friend's house later that evening

assisting with dinner, when a loud angry voice arrived in the front room. The

visitor had had it with this country; he was leaving. Everyone in the room

paused and asked him what the problem was. He told them that today, he was

stopped by a policeman and had to pay a $50 bribe because he didn't have a

"vaccination certificate" for his truck.

The coast of Tanzania greets me, and I smile. I smile because I know that

wherever I land down there, someone is going to try to get me. I don't have a

flight clearance for this country. I sent about 10 requests over the preceding 2

months from all sorts of places, and in the Comoros, I sent another and stamped

it and signed it and put several official numbers on it. Now, I am ready for

battle on the ground. Tanzania used to be called Tanganyika - which means

the bush beyond Tanga (a coastal town). When Tanganyika and the island Sultanate

of Zanzibar united, the country became Tanzania. They have never really been

united though, so I see this as an opportunity to land in a place where the

right hand (Tanzania) doesn't know what the left hand (Zanzibar) is doing.

I have never had a great desire to go to Zanzibar, and yet so many people

have asked me if I have been there. This is supposed to by a mystical and

ancient place, but I am very worried that I have arrived with an expectation. An

woman named Helle tells me that five years ago there were travelers here, but no

tourists. Now, there are tourists, and it is a different place. She is seated

with an Italian Doctor named Mario over breakfast. Fatur is the Arabic

word for breakfast, and one of the popular replies here when you ask when

someone will be back is baad al fatur (after breakfast). Mario tells me

that his favorite expression is "I'll be back in five minutes." He posts this on

his door. "I won't be," he tells me, "but the important thing is that they not

lose hope."

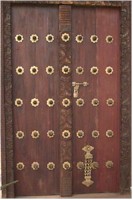

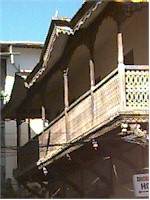

As I wind my way down tiny

streets that open into little market squares, I recognize the Portuguese style

of wood screened balconies hanging overhead. The Portuguese occupied this island

in the 16th and 17th centuries, and on the neighboring island of Pemba, when the

ground is hard in December and February, the local people still practice

bullfighting. It is more of a game than a fight though, and the bull is not

killed. Along the streets, strong dark doors of oiled teak are brightly adorned

with great brass studs. Along the surrounding frames and lintels, there are

elaborately carved motifs. The lotus and the fish symbolize fertility; the date

is for plenty; the frankincense tree is for wealth, and the chain is for

security. I almost feel like I am in a gigantic maze as I debauch from one

narrow street into another, and I enjoy not knowing where I am going nor how to

get there.

As I wind my way down tiny

streets that open into little market squares, I recognize the Portuguese style

of wood screened balconies hanging overhead. The Portuguese occupied this island

in the 16th and 17th centuries, and on the neighboring island of Pemba, when the

ground is hard in December and February, the local people still practice

bullfighting. It is more of a game than a fight though, and the bull is not

killed. Along the streets, strong dark doors of oiled teak are brightly adorned

with great brass studs. Along the surrounding frames and lintels, there are

elaborately carved motifs. The lotus and the fish symbolize fertility; the date

is for plenty; the frankincense tree is for wealth, and the chain is for

security. I almost feel like I am in a gigantic maze as I debauch from one

narrow street into another, and I enjoy not knowing where I am going nor how to

get there.

The problem is there are

too many people here, I am told. There are now 800,000 people living on the two

islands of Unguja and Pemba. Zanzibar, the capitol, is located on Unguja, and

here it is normal for a woman to have 8 to 9 children. Tourism has not helped.

There are now more immigrants, more people and more crime. Kirstin Siex has been

studying Colobus monkeys here since 1992. She is interested in population

ecology and how this relates to forest ecology. Forests in Zanzibar are being

cut down and the monkeys are being hunted as pests. The Jozani reserve is about

2,300 hectares (23 sq. km.), and the red Colobus monkeys there will come right

up to you; they are incredibly habituated. "The problem with habitat destruction

is that the animals come closer to cultivated areas," she tells me. Kirstin has

noted higher aggression within and between groups along the agricultural strips

cultivated by humans. It is a situation of crowding and overgrazing, she

explains.

The problem is there are

too many people here, I am told. There are now 800,000 people living on the two

islands of Unguja and Pemba. Zanzibar, the capitol, is located on Unguja, and

here it is normal for a woman to have 8 to 9 children. Tourism has not helped.

There are now more immigrants, more people and more crime. Kirstin Siex has been

studying Colobus monkeys here since 1992. She is interested in population

ecology and how this relates to forest ecology. Forests in Zanzibar are being

cut down and the monkeys are being hunted as pests. The Jozani reserve is about

2,300 hectares (23 sq. km.), and the red Colobus monkeys there will come right

up to you; they are incredibly habituated. "The problem with habitat destruction

is that the animals come closer to cultivated areas," she tells me. Kirstin has

noted higher aggression within and between groups along the agricultural strips

cultivated by humans. It is a situation of crowding and overgrazing, she

explains.

About 10,000 years ago, Zanzibar was part of the mainland. This is how the

leopards, civets and monkeys got out here, because they didn't swim. Then the

sea level began to rise, and they were cut off. Throughout the wooded paths of

the island, I come across little roadside shops selling various spices (cloves,

cumin seed, saffron, ginger, vanilla, cinnamon, turmeric, pili-pili, nutmeg,

tanduri, curry powder, cardamom, black pepper, and lemon grass). Zanzibar has

long been famous for cloves. These dried unopened buds from the tree are used

not only for cooking but in the pomme d'ambre to keep linen smelling

fresh. Kirstin explains that 80% of the medicines in the world use natural

products. I pull a shokishoki (rambotan) off a tree, as instructed, pop

it open, and eat it. It is delicious. I have never seen one of these before, let

alone eaten it. Our conversation moves to a higher level as Kristin tells me

that we are anthropocentric; we want to reproduce and survive. Look at

Christianity, Communism and Conservation; we are engaging in philosophies to

look after future generations - not just our own clan. But all of these things

have failed, because they defy the self-gene concept. It defies survival of the

fittest if you are looking after other things. I am trying hard to understand

this sudden shift in levels of conversation, but then she looks at me and says,

"You don't survive here unless you learn patience." We are back in Zanzibar.

"Here, just trying to get something done is a day to day struggle."

Back at the airport, I am greeted by Ali Mohammed, the airport manager. He is

very impressed by my stamped and signed copy of the clearance from Comoros. I am

charged a $40 landing fee instead of the $300 entrance fee required in mainland

Tanzania. We part with the traditional Swahili Hashima - the left hand

grasping the right elbow, our right hands clasp, and I say, "Kwaheri"

(good-bye).

Tom Claytor