08 Jul 1996 - Serengeti, Tanzania

All across this land remain the names of places that the Maasai have given

them. Ngorongoro means the place with mountains and gorges.

Oldupai is the wild sisal that grows in the Olduvai gorge, and

Siringet is the Maasai word for a vast place. From the northern edge of

the Ngorongoro crater, I follow the 90 meter deep and 50 kilometer long Olduvai

gorge west into the Serengeti. The first time I ever came here, I didn't have a

map. A bush pilot and filmmaker named Alan Root drew me a map on a piece of

scrap paper. There was a bump on the horizon and a line for a road. He put a dot

where the road intersected a river, and that he said was where I would find the

airstrip.

This place is not so

different from his map. It is simple. There is a sea of yellow, and a sky of

blue. Perhaps, it is because the colors are complimentary to each other that

makes them so powerful together; the one magnifies the other in a surreal way

that makes me feel like I am floating between heaven and earth. Amidst the

endless tawny yellow below are the distinctive island kopjies of the

Serengeti. These little rock islands are mini ecosystems with birds, lizards,

hyraxes, and sometimes, a resident leopard. There are no trees, and you can see

the wind flowing like waves across the grass.

This place is not so

different from his map. It is simple. There is a sea of yellow, and a sky of

blue. Perhaps, it is because the colors are complimentary to each other that

makes them so powerful together; the one magnifies the other in a surreal way

that makes me feel like I am floating between heaven and earth. Amidst the

endless tawny yellow below are the distinctive island kopjies of the

Serengeti. These little rock islands are mini ecosystems with birds, lizards,

hyraxes, and sometimes, a resident leopard. There are no trees, and you can see

the wind flowing like waves across the grass.

I land at lake Ndutu to

visit Baron Hugo van Lawick. I first met Hugo when I was working on a film

called "Serengeti Dairy" for National Geographic. The film was a celebration of

his 25th year living and filming wildlife in the Serengeti, and I was part of

the crew that tried to capture this place from the air. I park the plane in an

empty cage designed to keep the hyenas and lions from chewing the tires, and

soon a vehicle arrives to collect me. When I arrive in camp, Hugo comes out to

greet me. He is in a wheelchair, and we sit by his tent looking out over the

lake and drinking tea.

I land at lake Ndutu to

visit Baron Hugo van Lawick. I first met Hugo when I was working on a film

called "Serengeti Dairy" for National Geographic. The film was a celebration of

his 25th year living and filming wildlife in the Serengeti, and I was part of

the crew that tried to capture this place from the air. I park the plane in an

empty cage designed to keep the hyenas and lions from chewing the tires, and

soon a vehicle arrives to collect me. When I arrive in camp, Hugo comes out to

greet me. He is in a wheelchair, and we sit by his tent looking out over the

lake and drinking tea.

The nice thing about this part of the world is that traveling is so difficult

that one does not usually get a lot of visitors. A visitor brings news from the

outside world, and this is something that one can yearn for. Hugo first came to

Africa in 1959, because he wanted to film animals. He came for two years, and he

never left. He made lecture films for Louis Leakey and at age 24 shot the

photographs for the articles on the Leakey's work in Africa. He was married to

Jane Goodall for 10 years, and he has spent most of his life observing and

recording wildlife through a lens. He is having trouble breathing with his

emphysema now, but he wastes no time in filling me in on what has been

happening. It seems all the wild dogs have all been exterminated by rabies

brought in by the Maasai dogs; the lion numbers are down due to feline

distemper, and so the cheetah numbers are up. The bat-eared foxes have been hit

by rabies, and the poaching is still bad on the western boundary. According to

Hugo, some people there have never tasted cow meat, only wild game meat. There

are snares everywhere along that boundary, and the park used to feel very big

when there weren't so many tourists. Hugo relays all this news as one might talk

about the traffic jams on the way to work, and I have to quietly smile as I

listen. He then tells me about the pilot Bill Stedman who crashed his motor

glider while coming in to land here last year. He was working on Hugo's film

"The Leopard Sun"; the plane just dropped out of the sky, and Bill was dead. We

both pause and looked out across the lake. I ask Hugo if he remembers when we

landed on that lake and built a fire on the edge as part of our "camping scene"

for the film. He remembers and chuckles about this. I was arrested shortly after

that back in Seronera by armed scouts. They took me to the park warden's office,

but I had no idea why. I was asked what I had done the previous day, and I

explained that we had been filming by the lake and had landed on its edge. A

little man confirmed that I had landed on the edge of the lake, and then I was

released because I had told the truth. I was still a little confused by all

this. I was told that they were going to "compound" me and the plane, but that

since I had told the truth, I would now only have to pay a fine. I shuddered to

think what this fine would be, but it was only 1,500 Tanzanian Shillings (about

$3).

I ask Hugo what he has learned out here. He tells me that he is calmer and

more self-assured now, but this is probably due to age. "You are alive thanks to

luck in many ways," he tells me. "How fragile life is." He explains to me that

if you are out here full time, it is not good. "You get tunnel vision and you

lose your perspective." Hugo has seen a lot of scientists and researchers pass

through here. When they arrive they have a lot of fear of Africa for about six

months, then they go completely the other way and become fearless. It is the

same with pilots, he says, and that is the most dangerous time - when they

become fearless. Hugo spent many years observing Chimpanzees when he was with

his former wife Jane Goodall. He tells me the good Chimp mothers would

discipline their young with a hit or a bite on the hand, followed by a hug

afterwards. This is how you should treat human children, he explains. Hugo and

Jane have a son named Grob, and he tells me that they never ignored his crying.

If you ignore their crying, they will become insecure. I am always interested

when anyone has advice on how to be a good parent. Silently, perhaps, I must be

longing for this.

Chimps, to Hugo, aren't animals; they are so close to humans. He tells me

about the tame Chimpanzee named Washoe in USA. It was asked to sort different

photographs into humans and animals. He put the photos of himself with the

humans, and he put the photo of his mother, who he didn't know, with the

animals. Hugo asks me, "If Neanderthal man were alive today, would we call him

human?" In captivity, Chimps that haven't been brought up in a group don't know

how to mate. Robondo is an island in Lake Victoria west of here. It is the only

successful complete rehabilitation in the world of domestic Chimpanzees back

into nature. Domestic Chimps know your strength; they will attack you. Wild

Chimps think you are stronger, so they will run. Robondo was set up as a refuge

for certain endangered species by Bernard Grzimek in the 60's. The Chimps were

just dumped there. All the original adults are now gone, but when Markus Borner

went there and pointed a camera lens at a female with a baby, she attacked and

injured him, so perhaps they haven't forgotten everything.

The mention of Robondo reminds me of a pilot friend that I had met in the

Serengeti. Tim Ward was one of those friendly people who would take the time to

help you. I only knew him briefly, but he helped me find my way around the

Serengeti during the film. I was shocked when I later learned that he had

crashed taking off from the 900 meter airstrip on Robondo. Everyone one board

was killed. I had filed this somewhere in the back of my head and was very

surprised to meet his widow some years later in South Africa. I got to know him

better by listening to her, and she said to me, "God takes young, those he loves

the most."

I leave Hugo and fly north to Seronera. This is the location of the park

headquarters and the research camp. Everyone in the research camp seems to have

a nickname relating to what they are researching or doing. There is "John

wildebeest", "Jane of the Serengeti", "Tracy balloon", "Sarah cheetah", "Sarah

rabies", "Sarah simba", and "the hyenas".

Sarah Durant has been here for five years researching cheetahs. Her project

is a long range one which involves tracking known individuals by spots and

markings. The mortality, birth rate, and different aspects of cheetah behavior

are recorded to predict how the population will behave and how the cheetahs fit

into the ecosystem. Sarah uses a sound system to play back lion and hyena sounds

to cheetahs in order to record their reaction. Sarah has observed that the most

successful cheetah mothers are the ones who move the farthest from the lion

calls. We travel out into the plains and set up the equipment near some

cheetahs. When the lion sound is played, the female cheetah looks up and

analyzes the sound. It then usually takes her about 15 minutes to then get up

and move from 500 meters to one kilometer away. Sarah takes a lot of time

recording the smallest details of behavior in her notebook and the times that

they occur. It almost seems to be over-analyzing their behavior to me until she

explains that only 5% of young cheetah cubs reach maturity due to predation by

lion and hyena, so the little details matter. Sarah plays hyena "whooping"

sounds through her speaker. This is a contact call which they make as they are

moving around. The "giggling sound" they make only when they are on a kill.

However, neither of these sounds seem to disturb the cheetahs as much as the

lion calls. The furthest distance that Sarah has been able to locate a cheetah

is 7.5 kilometers. She has to find them with binoculars first, then she can

follow and observe them. 90% of the cheetah's diet is Thompson's Gazelle, so

most often, you will find them perched up on an old termite mound surveying the

horizon. Sarah tells me that she wants to find out what is best for the cheetah

in the long term. "You don't want to encourage them being pets. This is what

wiped them out in Asia; the Maharajas used them for hunting."

Sarah tells me that the Tanzanians have no concept that tourists should get

something for their money when they come here. "Just look at the menu and how

much you have to pay to stay in the lodges here," she says with a smile, and

yet, this is also what Sarah likes the most about this place - that it just

doesn't matter. "I think people need something beautiful in their lives and

wilderness is beautiful - like art and culture. This is why this place is

important," she says. When you sit out in the wilderness all day looking at

nature all around you, you begin to realize this. She tells me that Coco Chanel

once said, 'Nature gives you the face you have at 20, but it is up to you to

merit the face you have at 50.' We all earn our face.

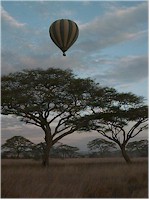

Long before the sun rises,

Tracy Robb and I have left camp to prepare her balloon. The clients arrive and

we are airborne drifting across the Serengeti. From up here, the Serengeti comes

alive. It is covered with animals. On the ground, the wind is from the south,

and as we increase in altitude the wind comes from the east. The higher we go

the more we turn to the left. This is how she steers. In the northern hemisphere

it is the opposite; you will turn to the right with height. Tracy is from South

Africa, and ballooning is her passion. I find my eyes are fixed to the ground as

we drift along. The wildlife below is looking up at us, not knowing whether to

watch or run as we pass.

Long before the sun rises,

Tracy Robb and I have left camp to prepare her balloon. The clients arrive and

we are airborne drifting across the Serengeti. From up here, the Serengeti comes

alive. It is covered with animals. On the ground, the wind is from the south,

and as we increase in altitude the wind comes from the east. The higher we go

the more we turn to the left. This is how she steers. In the northern hemisphere

it is the opposite; you will turn to the right with height. Tracy is from South

Africa, and ballooning is her passion. I find my eyes are fixed to the ground as

we drift along. The wildlife below is looking up at us, not knowing whether to

watch or run as we pass.

Back on the ground, I am starting to notice that there are more female

researchers than male researchers here. I feel a little bit like a Thompson's

gazelle surrounded by cheetahs, and I am not sure that I am very comfortable

about it. This surprises me, because I would have imagined that I wouldn't mind

the attention, but this is different. I think males naturally like to hunt their

prey or their mates, but they aren't so keen to have it the other way around. I

find myself trying to avoid places and situations where I might be hunted. This

is certainly a new experience for me, and I soon find security with John

wildebeest.

John tells me that before the drought of 1993, there were 1.6 million

wildebeest. Now, there are .9 million. There are a quarter million zebra and a

half million Thompson's gazelle. John conducts his research by putting grass on

a one meter square platform sled and dragging it up to a group of gazelle. He

doesn't stop his vehicle, so as not to frighten the gazelle, but he releases the

sled. The idea is that the gazelle will then come up and feed off the sled. He

can then compare the weight of the grass before and after they have fed. So far

this hasn't worked, because the gazelle haven't fed of the platform, but John

remains optimistic.

Late in the afternoon, I sit

east of Seronera and watch the sun set over the horizon. After the sun goes

down, the sky turns a brilliant red as the sun shines up on the base of the

clouds. Normally, the sun sets quite quickly along the equator, but this red

glow continues for a full 15 minutes as the surrounding darkness envelopes me.

This is taking far too long. I study this until I become convinced that I have

made a great discovery. The sun must surely be reflecting off of Lake Victoria

like a mirror and bouncing back up into the sky. I cannot imagine any other

explanation for what I am seeing, but unfortunately no one thinks this is

possible.

Late in the afternoon, I sit

east of Seronera and watch the sun set over the horizon. After the sun goes

down, the sky turns a brilliant red as the sun shines up on the base of the

clouds. Normally, the sun sets quite quickly along the equator, but this red

glow continues for a full 15 minutes as the surrounding darkness envelopes me.

This is taking far too long. I study this until I become convinced that I have

made a great discovery. The sun must surely be reflecting off of Lake Victoria

like a mirror and bouncing back up into the sky. I cannot imagine any other

explanation for what I am seeing, but unfortunately no one thinks this is

possible.

Markus Borner is preparing

his plane to go and track lions. He tells me that last night an elephant wanted

to sit on my plane. The askaris had to fire shots into the air. It was the same

elephant that had wrecked the boats and the land rover. The boats were wooden

canoes confiscated from poachers all lined up in a row. The elephant walked down

the whole row and crushed them. The land rover it turned over with its tusks. He

is a solitary bull, and he is a bit mischievous. Markus works for Frankfurt

Zoological Society here, and during the "Serengeti Diary" film, we flew together

in formation across the wildebeest migration. I could only see him half the time

as he was beneath my nose, and I had to watch him on a small television screen

through the camera as we were flying. He called these film runs the "National

Geographic Air Force maneuvers", and we would whiz past kopjies and trees and

wildebeest like feathers in the wind. Markus is old fashioned. He believes there

should be places on earth where man is not. He also thinks that conservation or

a national heritage is a sounder base than just revenue. "It should be pride,

not money," he says. Markus knew Professor Bernard Grzimek, and he says that

Grzimek trusted the Africans and believed in them; it was not just money for

them. At the time of independence, there was just one national park in Tanzania.

Now, there are 12 national parks and 1 Ngorongoro conservation area. Markus

says, "I learned through Grzimek to listen to older people. It is worthwhile to

listen. Wilderness is an emotional thing, and emotion is important for us. We

always try to find a rational reason for things; emotion is more important." He

refers to Grzimek's chapter heading - "listening to a lion roar". "We have had a

wave of rationalizing since then, but now emotion is coming back."

Markus Borner is preparing

his plane to go and track lions. He tells me that last night an elephant wanted

to sit on my plane. The askaris had to fire shots into the air. It was the same

elephant that had wrecked the boats and the land rover. The boats were wooden

canoes confiscated from poachers all lined up in a row. The elephant walked down

the whole row and crushed them. The land rover it turned over with its tusks. He

is a solitary bull, and he is a bit mischievous. Markus works for Frankfurt

Zoological Society here, and during the "Serengeti Diary" film, we flew together

in formation across the wildebeest migration. I could only see him half the time

as he was beneath my nose, and I had to watch him on a small television screen

through the camera as we were flying. He called these film runs the "National

Geographic Air Force maneuvers", and we would whiz past kopjies and trees and

wildebeest like feathers in the wind. Markus is old fashioned. He believes there

should be places on earth where man is not. He also thinks that conservation or

a national heritage is a sounder base than just revenue. "It should be pride,

not money," he says. Markus knew Professor Bernard Grzimek, and he says that

Grzimek trusted the Africans and believed in them; it was not just money for

them. At the time of independence, there was just one national park in Tanzania.

Now, there are 12 national parks and 1 Ngorongoro conservation area. Markus

says, "I learned through Grzimek to listen to older people. It is worthwhile to

listen. Wilderness is an emotional thing, and emotion is important for us. We

always try to find a rational reason for things; emotion is more important." He

refers to Grzimek's chapter heading - "listening to a lion roar". "We have had a

wave of rationalizing since then, but now emotion is coming back."

Tom Claytor